Making the Most of Post Mortems

Making the Most of Post Mortems

Mike Crittenden | Senior Software Architect

April 29, 2016

You're woken up at 4am to the lovely sound of your phone ringing. You answer, and a robotic voice tells you that an outage has been detected on your current project's site and you're the person on call this week, you lucky duck! You roll your grumbling self out of bed, plop into your computer chair, and get to work, staring at the screen through half-open bloodshot eyes. It turns out that trying to submit the contact form is causing the site to churn and eventually timeout. This is a Really Bad Thing because the site happens to be for a Japanese Healthcare company and right now it's the middle of the afternoon in Japan, the peak time for users to be trying to contact the company. The users are angry, which makes the client angry, which leads to a 4am wakeup call that makes you angry.

After a cup of coffee and an hour and a half of digging through backtraces, you eventually figure out that yesterday's deploy included a typo in the CRM URL setting in one of the settings files. This meant that contact form submissions aren't able to reach the CRM, and instead just spin and eventually timeout. Why wasn't this caught right when the deploy went out, you ask, or better yet, in QA or UAT? It turns out that this settings file is only used on production, and not only that, but it's only used when traffic increases during peak hours and the load balancer starts routing it to the server that uses this settings file. So the problem didn't exist on the staging environment, and it didn't even exist on production until peak hours hit. Tough break. You fix the typo, push a hotfix release, and all is well with the world. You're able to lay back down for 15 minutes before your alarm goes off to get the kids ready for school.

Step 1: Breathe, don't blame

You're probably pretty upset at this point. You're upset at the person who made the typo, upset at the code reviewers who approved the pull request, and maybe you're even upset at whoever's decision it was to architect a system where there is a settings file that is only ever used or testable during peak hours on production.

Don't do that. There is nothing good to gain from that. In fact, there is a lot of bad to gain from that.

Blaming implies that the human mistake was the root cause

The whole premise that it's someone's "fault" is flawed from the start. If you consider a human mistake to be the root cause of whatever just broke, then you're just wrong. The root cause is never a human mistake. Human mistakes are a given, not an exception. Humans make mistakes, and we know this about ourselves. Mistakes should be planned for and projects should operate under the assumption that they will happen. It's nobody's fault that things broke due to a mistake. Rather, it's everybody's fault that the project is architected and built in such a way that the mistake was allowed to happen and allowed to cause so much damage.

Blaming leads to CYAE (Cover Your Ass Engineering)

If you make everyone aware that things broke because James and Tyler screwed up, then the next time anyone on the team makes a mistake (and it will happen, because they are human beings), they will try hard to cover it up so they don't get blamed and shamed. Or even worse, they'll build things in a way that gives them an "out," or a way to blame something or someone else if that thing breaks. This is the opposite of productive. It means that we can't learn from each other's mistakes. It means that we are wasting valuable cycles building things in a way that prevents us from getting in trouble if they break. It means that we're scared and stressed, all because someone screwed up that one time 2 months ago and caught some heat for it. There's a lot of power in feeling like you can report your screwups to the team and that you won't be judged or blamed or scolded for them, and instead it will be used to improve things. It's great for morale, team building and camaraderie, and the project health as a whole.

Blaming leads to missed opportunities

If you fix something that breaks, then you've been given a golden opportunity. You were just given a shining example of something that needs to be improved about the project. If you choose to respond by pointing your finger at someone, then you're missing out. Make that mistake impossible to make in the future! Add monitoring to ensure that that mistake gets caught immediately next time! Use it as a way to make your project better, stronger, more robust, rather than a way to make someone feel bad.

Step 2: Write up the post mortem (alone)

Hopefully now that you've taken some time to calm down and you've realized that finger pointing is not the answer, you're able to think a bit more clearly. This is a good time to write up the section of the post-mortem that explains what broke and how you fixed it, since it's still fresh in your mind and your mind isn't clouded with grumpy thoughts. Here are some tips for this part. Stick to the facts. Write exactly what happened, from the triggering event (i.e., you being woken up at 4am) to the resolution (i.e., your hotfix being pushed out and confirming that it worked). Feel free to include information about ideas that were disproven and debugging steps that yielded no results. These can help bolster confidence that your resolution fixed the root cause. Be careful to avoid recommendations or predictions at this point. That stuff comes later. If it's not a fact, then it doesn't belong here just yet. Include a timeline. Look back through your browser history or your terminal or your IM sessions or emails to get as close to a precise timeline as possible, at least for the major events. This can often come in handy later for things like identifying if the client's brother's friend's submission failed because it was during the outage or because something else could be broken. Explain the impact. How many users were affected? What did traffic look like at that time? How long was the issue occurring, exactly? How many users actually complained? Is there any way of retrieving the lost form submissions, perhaps in the logs? Are you able to translate that to monetary loss? In other words, what's the real value lost to the client and/or the users?

If you're having trouble with finding the impact beyond a surface level, one tool you can use is the Appreciation Process. This involves starting with the problem ("contact form submissions timed out") and continually asking "So what?" This can be useful in making sure you fully appreciate all of the repercussions of this problem. Using our example:

Problem: Contact form submissions timed out.

- So what? The company didn't receive valuable contact requests sent by users.

- So what? Users got angry that they had to resort to using the slow automated phone system.

- So what? Angry users swarming the phone lines caused people to have to wait a long time to talk to a representative.

- So what? This affected users beyond the initial batch of people who had failed contact form submissions, spreading to a larger group.

- So what? A higher percentage of these users than normal canceled their service out of frustration, which lost the company $X dollars above the normal range for that day and time.

Don't feel like you need to limit each "So what?" to just one answer. You can have multiple answers at any level and create more of a tree out of it if that's helpful. Use some common sense about which answers are worth following deeper and which aren't.

Step 3: Find the root cause (together)

Now that you have all the facts documented, it's time for the fun part. Schedule a call with the relevant people on your team. On this call, you'll want to start out by making it very clear that a human mistake was made, and nobody is to blame. Explain that anyone on the team can and will make mistakes, some of which may be worse than this one. Frame it as an opportunity to improve. Once everyone is clear that this is going to be an open and honest discussion and that no blame will be involved, walk everyone through the post mortem doc you wrote up. Make sure everyone is clear on exactly what happened, what you did to fix it, how long it took, and what the impact was.

Now that everyone understands the details, it's time to get to the meat of the discussion. For the rest of the meeting, you'll probably want to focus on finding the answer to a few simple questions, which I'll provide some tools for below:

- Error Prevention: What made this mistake possible? What set of circumstances or processes (or lack thereof) led to this mistake? This is often called "Root Cause Analysis" and we'll talk through some tools for it below.

- Error Detection: What kept this mistake from being caught after it was made? What logging or QA or monitoring needs to be added or altered to catch it earlier? Why was the error allowed to do so much damage?

- Cost vs. Value: What would it take to detect or prevent this mistake in the future? Are we sure that implementing the "best" prevention or detection is really worth the effort involved? If a mistake takes 1 month of work to really prevent but only 10 minutes to fix if and when it pops up, then it doesn't really make sense to spend a month preventing it, and you should look for a simpler option.

Notice that you're attacking it from both sides: prevention and detection. You want to prevent the car from leaking oil, but you also want to keep the engine from blowing up if the oil does find a way to leak. Let's talk through some tools for answering those questions.

Tool: The 5 Why's

There's a lot of theory and history to this method, but the gist is that you start at the top with the issue that you saw, and ask "Why?" about five times, until you get to what seems to be the root cause. Using our settings file typo outage as an example, it could look like this:

Problem: Contact form submissions caused site timeouts and were never received.

- Why? The CRM was not be reachable from one of our production servers.

- Why? The URL of the CRM was incorrect in the settings file, so the site timed out trying to communicate with it.

- Why? A developer had to alter the settings file to update CRM URLs and made a mistake on that one.

- Why? The developer who worked on that had to alter dozens of settings files, causing it to be easily missed.

- Why? We have a settings file per environment and per site for this platform, which adds up to a lot of settings files.

In that situation, we went from the problem (site timeouts) all the way down to the root cause (we have too many settings files, which aren't manageable). Notice that we skipped right by the "blame" step (i.e., "developer made a mistake," which is only Why #3 in our case) because stopping there isn't helpful at all. It's important to note that the 5 Why's isn't an exact science. It doesn't have to be exactly 5, although 5 is generally a pretty good number to force you to dig deep but to prevent you from going down to absurd "because computers were invented" levels. There aren't any specific rules about how to decide what the answer to each Why is. Because of this, the outcome can vary depending on factors like the specific people involved in the discussion and their roles, experience, and knowledge.

It can sometimes also be helpful to add a separate "Why wasn't this caught?" question for each stage, so that you're thinking both about prevention (the "Why?") and testing/monitoring/error catching (the "Why wasn't this caught?"). You may also run into situations where there isn't a single answer to each "Why." For example, maybe the answer to why the CRM request timed out could be because the URL was incorrect AND because there isn't any intelligent error handling to handle that gracefully and log the error, rather than bringing down the site. In that case, you can either just have multiple 5 Why's to explore the other avenues, or go into a full-on Why-becuase analysis.

Tool: Why-because Analysis

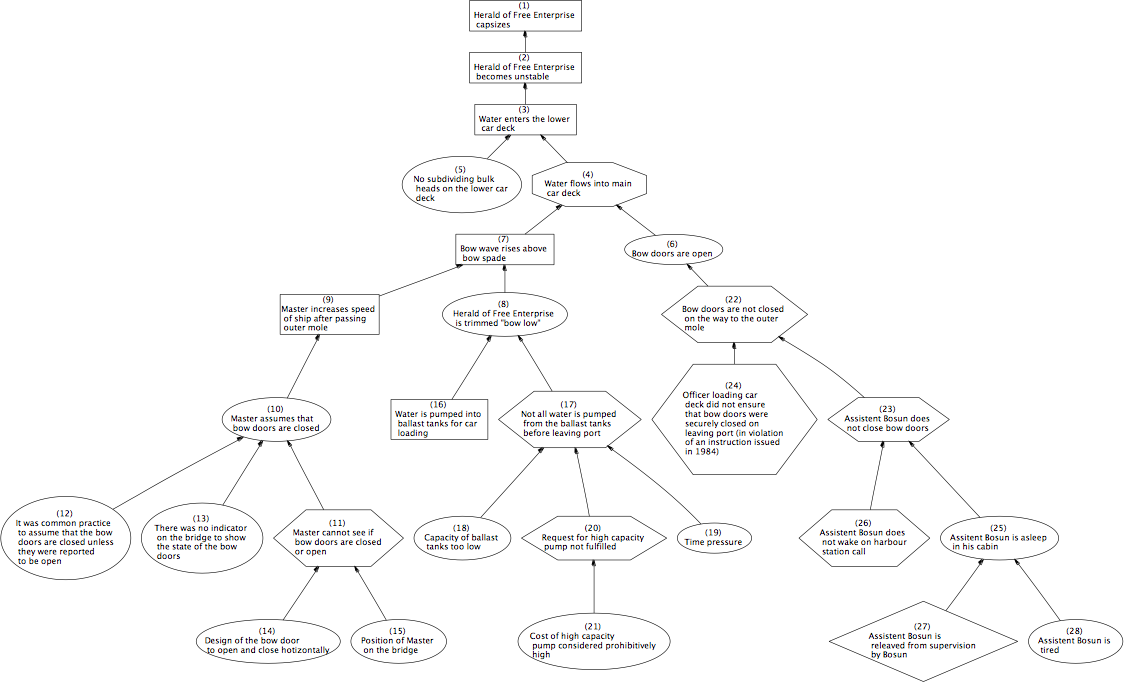

If you're finding multiple answers to the "Why's" then you may want to create what's called a "Why-because Analysis," which is just a fancy name for a chart that shows the multiple causes for each step, on down the line until you have a final set of root causes (as opposed to just one). An example image might help:

This image, stolen from Wikipedia, is the Why-because Analysis analyzing what caused the Herald of Free Enterprise to capsize in 1987. Note that the top level is the initial problem, and the bottom levels are the root causes, just the same as with the 5 Why's. The difference is that for each step we can split off into multiple causes. This way, we can capture all of the root causes in a single place, instead of splitting off into multiple 5 Why's, which gets confusing. This can get chaotic, but it's often an important exercise because in a complex system, there's rarely a single root cause with no other contributing factors. There are usually at least a couple other things going on that led to your problem.

Tool: Fishbone Diagram

Another option for finding the root cause(s) is the Fishbone or Ishikawa Diagram, which is a very different take on the problem. With this technique, you write the problem off to the right and then draw a sort of fish skeleton looking thing branching off of it. It should look something like this example:

The idea is that for each of the "bones" you should add a category, and then inside those categories you brainstorm possible causes within that category. The categories could look something like this:

- People

- Methods/Processes

- Tools/Software

- Environment/Conditions

- Resources/Documentation

Looking back at our situation, if we were talking about the "Processes" category, some causes we could list would include:

- No QA process for production settings

- Code review process lacking thoroughness

- Process for updating settings is overly complex

See where are we going with this? Fishbone diagrams are a good way to force yourself to think about each category of things that could contribute to the issue, instead of just the ones that are immediately apparent.

Step 4: Put it to action

Now that you have your root cause(s) that everyone agrees upon, it's time to fix them. Brainstorm a few options for fixing each root cause, and talk through each one with the team. In our example, some options for fixing the root cause of having too many settings files may be:

- Refactor the settings files to share more code so that there's less duplication, making settings changes in the future touch less files

- Consolidate non-prod environments (sandbox, staging, QA) to use the same settings instead of separate files

- Create a fake prod environment that allows you to test settings changes to prod-specific settings files, without deploying to prod

Let the entire team shout out as many ideas as they can, then work through the list and try to get a consensus together about which ones are best. I've found that the "right" answers are often fairly apparent by this point, and there's usually not much arguing to be had, but it's still important to look at all the options. If you're tempted to just go with the first thing that everyone comes up with instead of asking for more options, fight that temptation. It can be very useful to force yourself to come up with at least 3 options, even if one seems like the obvious choice. This is sometimes called the Rule of Three. And you're done! You've turned a major screwup into a major win. Doesn't that feel good?